In 1976, Carlo Cipolla, a professor of economic history, outlined five fundamental laws governing stupidity - a force he perceived as humanity’s greatest existential threat. He divided humanity into four buckets, as many of us are prone to do. The intelligent, the hapless, the bandit, and the stupid. The intelligent whose actions benefit both self and the other (win-win); the bandits who play zero-sum games where the outcome benefits them at the expense of others (win-lose); the hapless whose actions enrich others at their own expense (lose-win); and finally, the stupid who play lose-lose games. Take a minute and stare at the picture below.1

In Cipolla’s words,

A stupid creature will harass you for no reason, for no advantage, without any plan or scheme and at the most improbable times and places. You have no rational way of telling if and when and how and why the stupid creature attacks. When confronted with a stupid individual you are completely at his mercy….

They are dangerous and damaging because reasonable people find it difficult to imagine and understand unreasonable behavior.

Let’s apply Cipolla’s framework to Trump’s tariffs, both announced and threatened.

How do Tariffs Work?

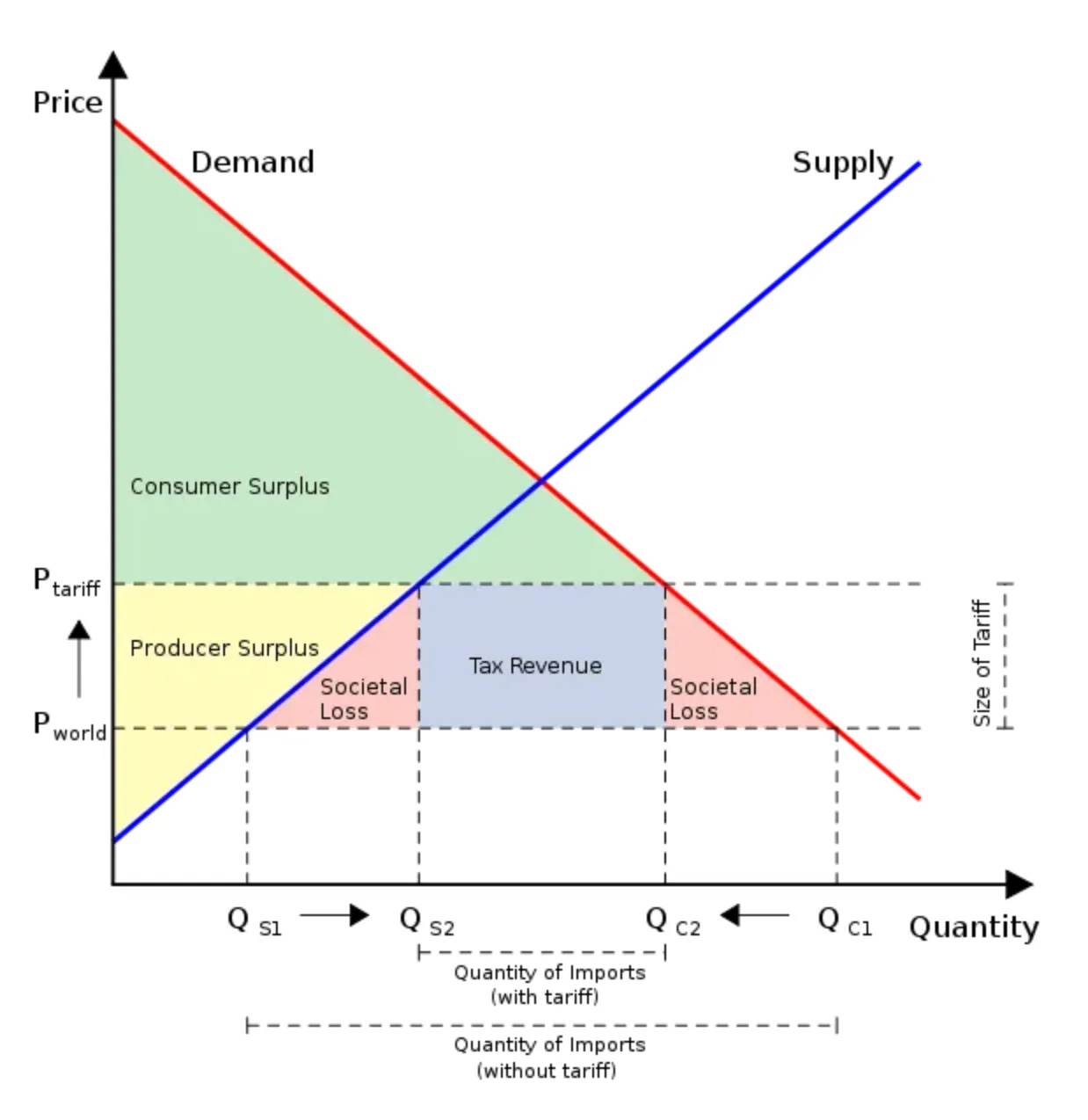

Welcome back to Prices & Markets with a dash of game theory. A tariff is a tax on consumers and a subsidy to domestic producers. See the picture below on how a tariff effects the importing country (USA if it imposes tariffs).

If this is boring, here is an intuitive recap: the tariff raises the price consumers face and that domestic producers can charge (from PWorld toPTariff). Consumers are worse off as consumer surplus declines, producers are better off2, and it raises tariff revenues. If you add all these up, you get the two red triangles showing a net loss to society. Overall, the loss to consumers outweighs the gains to producers and the tariff revenue.3 The red triangle on the left shows that the tariff distorts the behavior of producers - inefficient producers find it profitable to produce. The red triangle on the right is the distortion imposed on consumers as they pay a higher price and demand less than under free trade.

What happens in the exporting country (China)? The price consumers face in the exporting country does not change, so it does not impact consumers; producers in the exporting country are squeezed out, so their surplus declines, and of course, there is no tariff revenue. This is a lose-lose situation, and we are in the stupid quadrant.

There is one crucial caveat. The tariff left world prices unchanged, and domestic prices (the price in the importing country) rose by the amount of the tariffs. This happens if the importing country is “small”— changes in its demand do not affect world prices. For such countries, the optimal tariff is zero. Think Singapore, Hong Kong, etc., whose import share in world demand is small, so whether they import more or less does not impact world prices.

Tariffs Imposed By A Large Country

But what if the importing country is large (the US is a significant source of demand)? Then it has monopsony power. Just as a monopolist restricts production to raise prices, a monopsonist restricts demand for a good to drive down prices. Think Apple. It uses its outsized buying power to squeeze the margins of its suppliers such as Foxconn.

A tariff would now drive PWorld down and therefore also PTariff. Without going into details, this reduces the distortion (the red triangles) and the tariff revenue goes up. The net impact on the importer is ambiguous. So should the US impose a tariff? It should if the export supply elasticity is low. Imagine that Apple’s suppliers don’t have a lot of options, so when Apple bargains for a lower price, they acquiesce. The more inelastic the supply, the more Apple will squeeze them (just like Apple would squeeze iPhone buyers and charge them high prices if demand for iPhones is inelastic.) The exporting country (say, China) loses out, and in fact, its losses exceed the gains of the importing country. The world as a whole loses out. We are in the bandit quadrant where the tariff benefits one large country at the expense of others.4

But that is not the end of the story. If China is a big buyer, and it is for pork and soybeans, it will do the same. And when both the US and China impose tariffs, we get a trade war. The size of the pie is smaller than under free trade. We slide into the stupid quadrant where both countries are hurt. Politicians have constituents clamoring for “protecting jobs” and “putting our country first.” Lowering tariffs unilaterally looks suspiciously like “weakness” and who wants to appear weak.

Notice this is a classic Prisoners’ Dilemma. Each “large” country’s dominant strategy is to “defect” by imposing higher tariffs. But when they do so, the resulting Nash equilibrium is a trade war that imposes significant losses on everyone, including themselves. This is one of the reasons the GATT/WTO exists5. It is a mechanism to get to the “cooperative” outcome where both large countries keep tariffs low—the size of the pie is bigger, and we move from the stupid to the intelligent quadrant.

Retaliatory Tariffs

As Trump steadily escalates tariffs, other countries are following suit. Canada, Mexico, the EU, and China have introduced or threatened retaliatory tariffs. A trade war between the US and any of these countries means we are in the “stupid” quadrant. Note that these other countries are perfectly rational to retaliate.

Australia, on the other hand, said that while U.S. tariffs on Australian steel and aluminum were unjustified, it would not retaliate with its own tariffs because “tariffs are paid by the consumers.”

Does this mean that the tariff benefits the US and hurts Australia so we are in the “bandit” quadrant? Unfortunately, no. Tariffs may benefit US steel producers but since steel is a critical input (economists call it an intermediate input) in many industries, it raises the costs in these industries. Producers in these industries are hurt as their costs rise (think US car makers,) as are consumers (buyers of cars) since price increases follow the cost increases. Any gains in the steel sector (including jobs) are far outweighed by losses in other industries. An important side effect is that car makers based in Europe and Asia benefit as they do not face higher costs. Therefore, a tariff on an intermediate good benefits foreign producers and hurts US producers and consumers. We are in the hapless quadrant.

Putting it All Together

Markets have finally woken up to the stupidity of Trump’s tariffs. Of course, this has hurt us all as trillions of dollars in stock market wealth have evaporated. The Dow is down 2.1%, the S&P 500 3.2% and the NASDAQ more than 4%. But the DAX is up 17%.

Millions of Americans voted for MAGA and instead got MAGGA (Make Germany Great Again). In the end, Trump’s tariffs aren’t just bad policy—they are predictably self-destructive. Do you agree with Cipolla - that stupidity is indeed humanity’s greatest threat?6

Of course, we span multiple boxes - sometimes intelligent, sometimes selfish bandits, often helpless and taken advantage of by others, and frequently ineffectual (think a collapse of a negotiation). The stupid, according to Cipolla, are paragons of consistency.

Producers can raise their prices without fear of losing customers because imports are more expensive because of the tariffs. Economists looked at Trump's 2018 tariffs on washing machines and found that more than 100% of the tariffs were passed onto consumers.

The red triangle on the left comes because it distorts the behavior of producers - inefficient producers find it profitable to produce. The red triangle on the right is the distortion imposed on consumers as they pay a higher price and demand less than under free trade.

This paper shows that large countries face less elastic export supply curves (have more monopsony power) and prior to or absent WTO constraints set higher tariffs. Of course, this varies by commodity. In aluminum and metal ores, the US is small relative to the world (less than 5% of world imports), while in furnishings, toys, and watches, the US is “large” (20% of world imports). Steel also has a high export elasticity so the optimal tariff is close to zero .

Economists refer to this as terms of trade externality. And the WTO as a way to escape from a terms-of-trade driven prisoner's dilemma.

In the next post, I shall highlight four other aspects. First, who pays and absorbs the tariff matters. Is it the exporter who accepts lower prices, the importer who pays a higher tariff inclusive price, or the consumer, to whom the retailer passes on the tariff increase? Or some mix of the three. Second, the dollar can appreciate, which offsets the impact of the tariff. This happened in the last trade war instigated by Trump, but the dollar is weakening today. Third, we distinguished between final goods and intermediate goods (the raw materials, machines, and inputs that firms import to make final goods) and I will look at how much of each is part of trade. Finally, faced with tariffs, companies (think Chinese companies) can relocate production to another jurisdiction (think Vietnam), which is not hit.

"Two things are infinite: the universe and human stupidity; and I'm not sure about the universe." (Einstein)

Pushan, your application of Cipolla’s framework to dissect the inefficiencies of tariffs is both clever and compelling—especially the prisoner’s dilemma lens that underscores the mutual harm of trade wars. Yet, I can’t help but wonder if political incentives complicate the picture: leaders often cater to short-term demands from vocal constituencies, even at the expense of long-term economic health, which might keep us trapped in the 'stupid' quadrant. Meanwhile, today’s tangled global supply chains add another layer—tariffs on intermediate goods can send unpredictable ripples, potentially blurring the lines between Cipolla’s categories. Could there be cases where tariffs, though inefficient, act as strategic leverage to renegotiate trade terms? I’d love to hear your take on how these factors might shift the analysis.