Imperialism on the Cheap

Surviving the Donroe Doctrine

On January 15, María Corina Machado walked into the White House and handed Donald Trump her Nobel Peace Prize medal. The Norwegian Nobel Committee promptly clarified that a medal can change owners but not the prize: “it cannot be revoked, shared, or transferred.” Trump, of course, treated this as a detail. He posted that Machado had “presented me with her Nobel peace prize” for the work he had done.

It is tempting to treat this as a farce. It is not. In the span of weeks, Washington has kidnapped a head of state in Caracas and seems deadly serious about taking Greenland. This is not the familiar lament that “norms are eroding” that people in tweed jackets harrumph about at conferences. It is a severe blow to the rules-based global order.

Russia’s tore a hole in that bargain when it invaded Ukraine in February 2022, widely understood as a textbook violation of territorial integrity. But the US was seen, at least by its allies, as the guardian of that order. If Washington now signals that sovereignty is negotiable, allies and partners will ask the only rational question: Is ours negotiable, too?

The rules-based order rests on one core idea: sovereignty. After World War II, countries explicitly put state sovereignty and territorial integrity at the heart opost-warst-war bargain to protect weaker states from stronger ones and to avoid the convulsions and bloodshed of the world wars. The memory of those horrors has faded, and the lessons memory-holed. The new message from Washington is simpler and cruder: sovereignty is not a principle. It has a price and is fungible.

The US operation in Venezuela creates cognitive dissonance. Nicolás Maduro was an authoritarian who rigged elections, brutally cracked down on protestors, and, along with Hugo Chávez, presided over the collapse of the Venezuelan economy. But you can welcome the end of an autocrat and still understand that abducting a sitting head of state is not a marginal adjustment in foreign policy. It is a declaration that rules are optional, that power comes first, while legal arguments are assembled later.

A Bet Gone Wrong

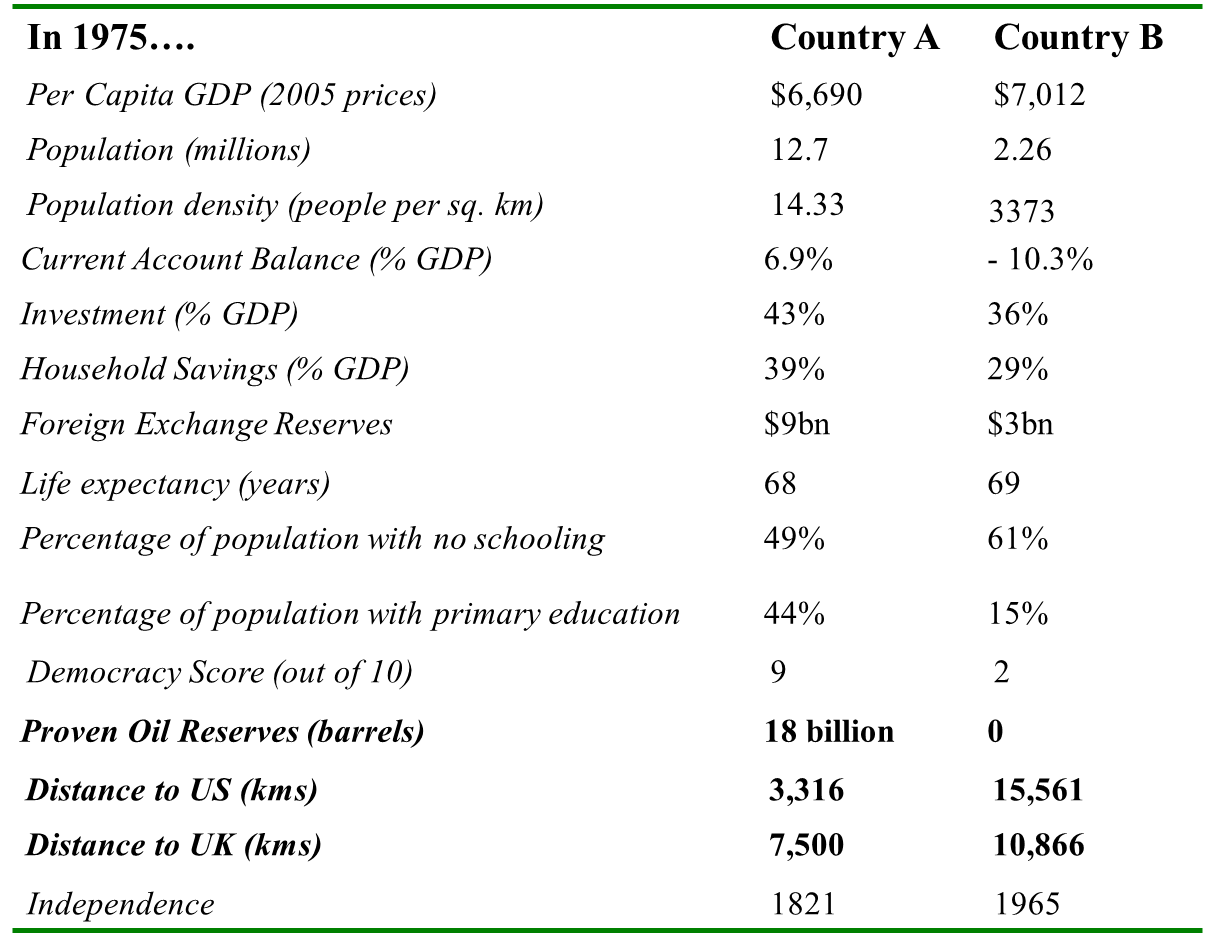

To see the tragedy of Venezuela, let me start with a bet. For years, I directed a program for Singapore’s Economic Development Board, and I would begin with a quiz. In 1975, which of the two countries would you bet on? (see data below).

The answer is clear - almost all would bet on Country A instead of Country B. Country B has no natural resources, high population density, is far from major trading centers (access to trade and supply chains matters), and scores low on democracy.

Of course, the bet would be catastrophically wrong. Country A is Venezuela, Country B is Singapore.1

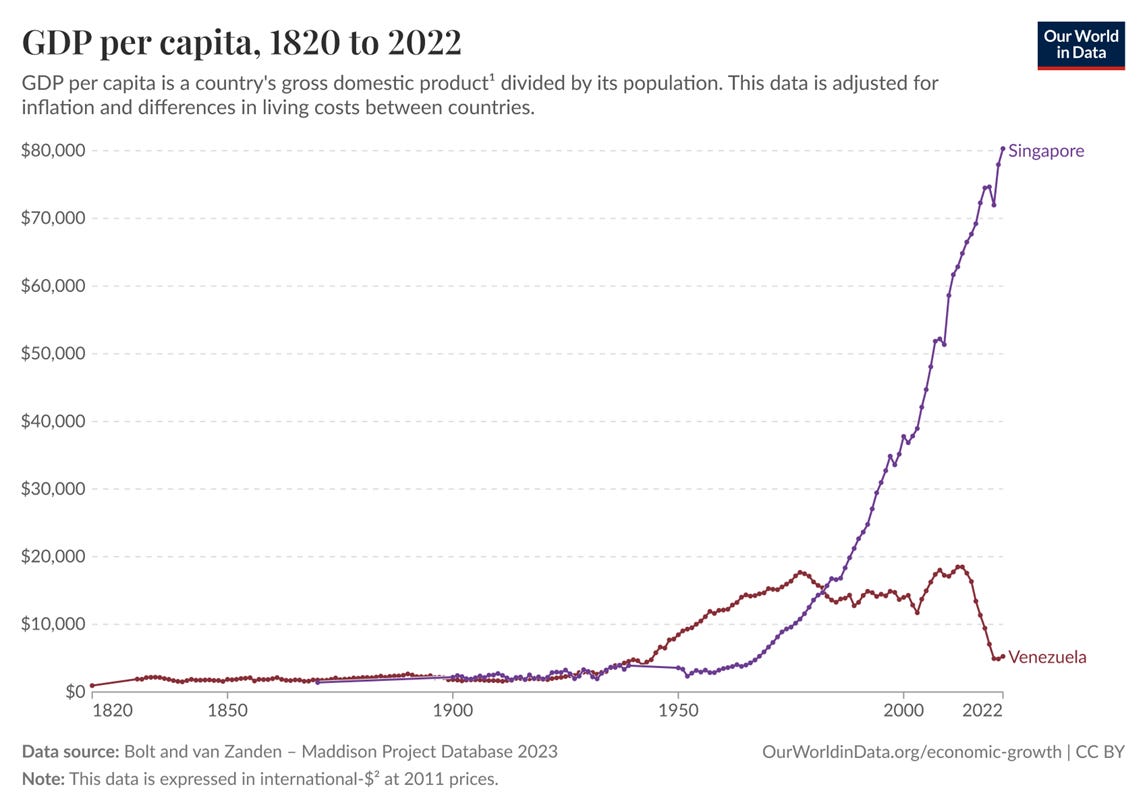

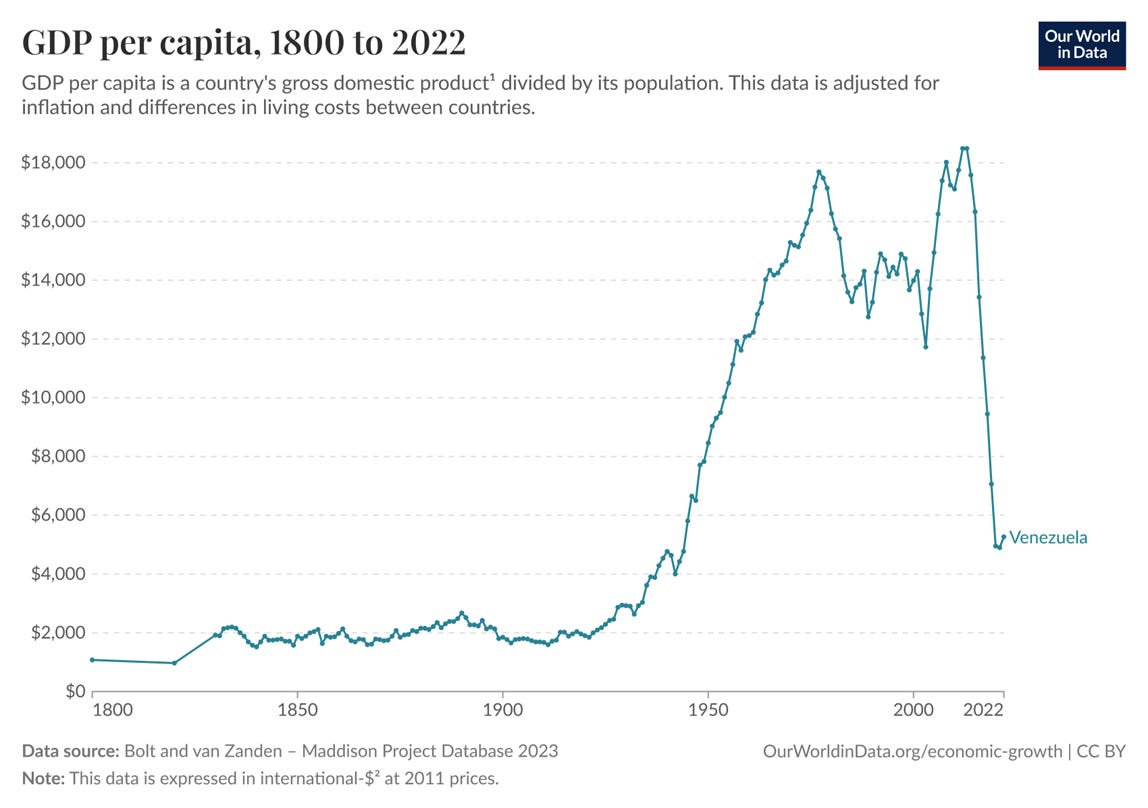

The collapse of the Venezuelan economy is obscured by the need to map Singapore’s growth on the vertical axis. So…

Many attribute the collapse to a single cause. For instance, Venezuelan economist Francisco Rodríguez argues that the US’s scorched earth sanctions in 2017 during the first Trump administration, triggered by an “uncompromising opposition,” decimated the oil industry but failed to initiate regime change. However, under Chávez and subsequently under Maduro, bad policies abounded and predated the 2017 sanctions. Most consequential was the mismanagement of PDVSA, which Chávez saw as a cash cow. Investments in PDVSA collapsed, its budget was raided to fund social programs and extract rents, and technocrats and engineers were fired. Pro-cyclical spending, double-digit fiscal deficits due to fuel and electricity subsidies, financed by loading obligations onto the state oil company (PDVSA), and monetary financing of deficits eventually triggered hyperinflation and a currency collapse. When oil prices started declining in 2014, the government responded with widespread expropriations, capital controls, and broad price and profit controls that crushed investment and domestic production. Venezuela’s oil turned out to be a curse. It fell victim to the Dutch Disease and lacked the institutions to benefit from its natural resources.

The Trump administration has trotted out a series of excuses for its kinetic intervention. Deaths from fentanyl (most of which come from Mexico, not Venezuela), ties to drug cartels (Cartel de los Soles is not a drug-trafficking network allegedly embedded within the Venezuelan state, but rather a loose network for patronage and profit), immigration with 700,000 Venezuelans in the US on a temporary protected status (but leaving the rest of the Maduro regime exacerbates the problem)2 and a quest for oil as Trump has repeatedly stated.

Oil is the common theme here - the reason investors would have bet on Venezuela in 1975, its mismanagement that led to Venezuela’s economic collapse, and the clearly stated rationale by Trump for removing Maduro.

So why is the US burning its diplomatic capital and the concept of sovereignty for a failed state? To understand the real reason, we must turn to the mysteries of chemistry.

Underestimating Venezuelan Oil

Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves, roughly 17 per cent of the global total, according to its own estimates, which must be taken with a pinch of salt. Yes, this is a thick, black sludge (extra heavy and sour) that is expensive to produce, an environmental nightmare, and requires massive investments over a decade. Venezuela’s oil production is currently below 1 million barrels a day, a fraction of its peak of about 3.4 million in 1998. Restoring Venezuela’s oil industry to its peak requires massive investment, estimated at US$10 billion to US$20 billion a year for a decade. Venezuela is uninvestable, according to Exxon’s CEO, who showed little enthusiasm in a recent meeting with Trump.

Best was a brutal and salty quote in the Financial Times from a private equity investor

No one wants to go in there when a random fucking tweet can change the entire foreign policy of the country”

But details matter…

Not all oil is the same. US shale oil is “light and sweet” and used to make gasoline to move humans, and naphtha to move heavy, sludgy oil in pipelines. Middle East oil is in the Goldilocks zone and yields a mix of gasoline, but importantly, diesel and jet fuel (used to move cargo). Venezuela’s oil, specifically from the Orinoco Belt, is “extra-heavy” and “sour.” As are the Canadian tar sands. They are best suited for asphalt used in construction. Venezuelan and Canadian bitumen yield roughly 60% of their weight per barrel of oil as vacuum residue (the thick, heavy, tar-like bottom product left after crude oil is distilled under a vacuum). Iranian and Russian heavy oils generate only 20%-30% vacuum residue.3 Demand in a modern economy is roughly split as follows: 40% Gasoline, 30% Diesel, 10% Jet, 20% Industrial/Asphalt.

Therefore, the following common statements should be taken with dollops of salt

Venezuela is responsible for less than 1 percent of the world’s overall oil output. Yes, but it is incredibly valuable for asphalt used in infrastructure.

Venezuelan oil makes up only 4–4.5% of China's imports. Yes, but estimates show it meets half of China's demand for bitumen used in asphalt.

The US does not need oil because of shale oil. No, shale oil creates gasoline. And its refineries are specifically designed for heavy oils.

Even Trump has realized this.

It is not just about where the oil sits and who you can sell it to, which is impacted by geopolitics (e.g., China-Venezuela, India-Russia) and sanctions. One key issue is whether you have the right refining capacity. US Gulf Coast refineries are specifically engineered with coking and hydrocracking units to convert Venezuelan sludge into diesel. In China, this is primarily done by teapot refineries, which import Venezuelan oil to crack it into asphalt. With Venezuelan oil shut off, the Chinese will pivot to the closest substitute, sanctioned Iranian oil (Iran Heavy) via Malaysia in the short-term, and eventually Canada.4

While this is speculation on my part, Mark Carney’s dash to Beijing and the sudden reset in Canada-China ties should be read in this light. China wants to diversify its supply sources. Canada wants to diversify its demand sources. Both are adjusting to the world as it is, not as we wish it to be. If Trump carries out his recent threats to attack Iran or seizes the shadow fleet carrying Iranian oil, as he did with Venezuela, or pressurizes Malaysia to cease being a conduit for China, the US gains another chokehold, albeit temporary, in the simmering economic conflict with China.

In sum, the Venezuelan operation was about oil, as Trump has repeatedly stated, and we should take him both seriously and literally. As long as Delcy Rodríguez makes a deal with Trump on oil and allows American oil companies to re-enter the country, the US will show scant interest in the plight of ordinary Venezuelans or in restoring democracy.

In this light, María Machado’s attempt to secure Trump's commitment to Venezuelan democracy by handing over her Nobel Peace Prize is tragic. She bravely tried to pretend it was an act of solidarity between two lovers of freedom, heirs to George Washington and Simón Bolívar. But Trump does not do solidarity. He does cards.

And this is the brutal asymmetry. Machado played the only card she had: The Nobel Prize. Once played, it cannot be played again. Delcy Rodríguez, on the other hand, can promise concrete deliverables: a pivot away from Cuba, thrilling Marco Rubio, reparations and a share in oil revenues to the US, contracts and access to Trump’s donors. Machado’s claims of popular support and legitimacy are too abstract for the Trump administration compared to the quick wins promised by Rodríguez.

Tragically, the opposition in Venezuela may fracture between those tempted to work with the US and elements of the post-Maduro regime and those who recoil at such a partnership. Machado was indomitable when standing up to Chávez and Maduro, but was not game-theoretic enough in her appeals to Trump. She saw her act as Strategy. To Trump, it reads as Tribute. And to others, as Surrender.

Donroe Doctrine

The original Monroe Doctrine was delivered almost in passing, a few sentences in President James Monroe’s 1823 State of the Union. Its claim was blunt: foreign powers should keep out of the Western Hemisphere, and any new interference would invite an American response. The US feared that continental European powers, specifically Russia, Prussia, Austria, and France, would intervene in Latin America to restore these colonies to Spanish rule. The core bargain was “Two Spheres”: the US would not interfere in European affairs, and Europe would not interfere in the Americas.

The “Donroe Doctrine” is imperialism on the cheap. A big contradiction lies at its heart: the administration claims it will dominate a sphere of influence from Greenland to Argentina, but it rejects the burdens that historically came with such claims, boots on the ground, governance, and the unglamorous grind of rebuilding states. Instead, the doctrine is about spectacle and submission. It favors short, cinematic, attention-grabbing operations, a quick declaration of victory, and then attempts to coerce the remnants into submission.

The deeper signal is that great powers are increasingly comfortable acting first and litigating norms later. This is not a formal license for everyone to carve the world into exclusive zones, but it lowers the political and legal price of trying. The system tilts away from rules and toward fiefdoms: the United States asserts primacy in the Western Hemisphere, Russia pushes harder in Europe, and China expects deference in East Asia. Even middle powers, India, Turkey, and Israel, will be tempted to impose their own regional hierarchies.

In this world, everyone will draw the lesson: hard power, plus economic leverage, is the currency that matters.5

Survival

Allies and partners of the US should start asking: if sovereignty is fungible in one region, could it be in another?

Countries like Singapore and Vietnam have long relied on a “balanced” model: economic ties with China, security ties with the US. But if the US is unpredictable or transactional, that insurance policy starts to look worthless. Why align with a distant power that might not show up, or where a “random tweet” can flip its entire foreign policy? Even NATO is starting to resemble a protection racket. “Nice island you got there; shame if something were to happen to it.”

So what can countries do?

First, get cracking, however tempting it is to adopt an ostrich-like posture. While there is no quick fix, nations should no longer see Trump or MAGA as a temporary anomaly. The world cannot be organized around the preferences of 40,000 voters in Wisconsin every four years.

Second, invest in hard power: technology, defense, trade, and manufacturing. That is the only currency that matters. Singapore’s strategy is to make itself indispensable, or at least too costly to swallow, what Lee Kuan Yew described as the poisonous shrimp approach.

Third, make new friends quickly and establish stronger economic connections, especially with neighbors facing similar constraints, and with middle powers like India, Brazil, and Turkey.

Fourth, prepare populations for pain and sacrifice. Leaders have to translate what this evolving order means in daily terms and build urgency, not just awareness. In practical terms, that means stronger fiscal positions, higher taxes, and budget shifts to shore up economic and military vulnerabilities.6 It can also mean compulsory national service and other visible commitments that signal resolve.

Finally, do not despair. Keep history in mind. With the notable exception of the United States in the 20th century, regional hegemons, from Imperial Japan to Napoleonic Europe to the Soviet sphere, have tended to overreach. Eventually, the costs of coercing the periphery exceed the economic value extracted. Hubris rises. Resistance adapts. Coercion becomes expensive. And the hegemon discovers that dominance is not the same thing as control.

Singaporeans often argue that we are a small country with no natural resources. To which I respond, you are lucky.

Following Maduro’s capture, the US Department of Justice unsealed a revised indictment that backed away from the term “Cartel of the Suns” as a formal organization.

Venezuelan (and Canadian) oil needs to be blended with light crude oil. Otherwise, it is too dense to be transported through pipelines to ports and exported abroad.

Russia produces “Urals” (Medium Sour), which is much lighter, with limited production and export of heavy oils. Chinese teapot refineries are optimized for Venezuelan heavy crude, another reason Russian oil will yield lower returns.

As Stephen Miller recently stated on CNN, we live in a world “governed by strength, force, and power” - the “iron laws of the world since the beginning of time.

And, of course, fewer CDC vouchers for Singaporeans.

Was looking out for that perfect primer that connected all the dots on Venezuala developments and here it is !! Thanks Pushan - this is extremely insightful !

Good read!