Democracy Discussion With INSEAD Audiences

One of the best things about INSEAD is the sheer national diversity of audiences I teach. Just this last year, I have taught participants from about 80 countries. One has to be exquisitely sensitive since we live in a world of great power rivalries, with conflict in Europe and Israel, and where the US and Western hegemony are being challenged by China and new groupings such as BRICS and the G-20. One of the most interesting and perennial discussions in class is on the value of freedom and democracy. How do I know that the audience finds this discussion interesting? After every module or session, I get detailed feedback on how the participants liked the content and the faculty. So what follows is loosely based on qualitative and quantitative data.1

Not surprisingly, this topic has attracted a lot of interest recently. Not only is there a great power game afoot, but 2024 is the year of elections. The UK, France, EU, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Taiwan, and South Africa all had elections this year. And the US elections are less than two months away. At the same time, we are living in a time of democratic backsliding.

Democracy: What is it good for?

In the classroom, I inevitably encounter whether democracy is good for economic growth and development. This is not an easy question to answer. I have some research on this, but even within academia, there is little agreement.

Among executive audiences, there is a grudging admiration and in some cases, even a longing for autocratic regimes[1]. To be more precise, benevolent autocrats. Where does this come from? I have some guesses. First, most large and mature organizations are somewhat autarkic. The vast majority of employees and even shareholders rarely get a direct say in its strategic direction.2 So, we admire strong leaders. The hagiographic coverage by the business press also helps. Think Henry Ford, Jack Welch, Steve Jobs, Peter Theil, Bill Gates, Ray Dalio, and of course, Elon Musk.

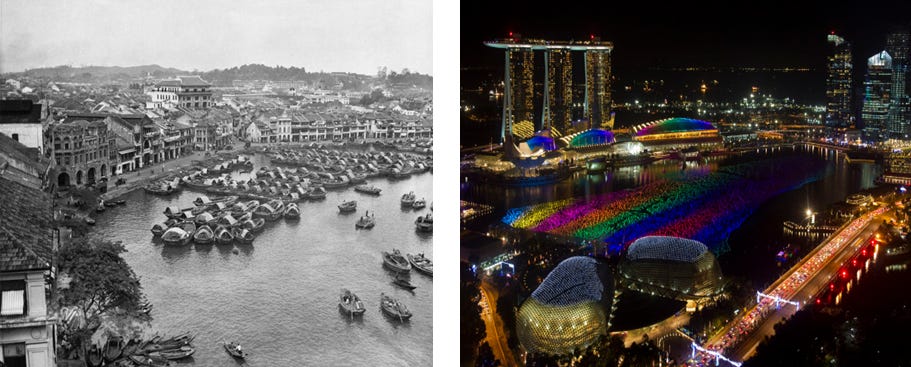

Switching to a country perspective, who does not want to live in a country with a visionary leader like Lee Kuan Yew. After all, the policies and the institutions he built are primarily responsible for Singapore’s spectacular success and transformation (see below).

From Kampungs to Casinos

Indonesia under Suharto experienced high economic growth, especially from 1983-1996, when growth was more broad-based and export-led. Chile under Pinochet, influenced by Milton Friedman and his ‘Chicago boys,’ experimented with neoliberalism and had decent growth rates in the 1980s especially compared to other countries in Latin America.3 But Chile’s performance improved only after Pinochet exited the stage when coalition governments led by Presidents Patricio Aylwin (1990-93) and Eduardo Frei (1994-99) broadened and deepened a wide range of "first-generation" reforms that had begun in the 1970s. And of course, China has had spectacular growth rates for for the last four decades.

Authoritarian governments have the ability to implement a long-term economic strategy, attract investment on a sustained basis, and make tough trade-offs. The short-term electoral cycles of democracies, on the other hand, are not conducive to long-term thinking, and leaders are prone to promising free lunches. The golden rule is that people love free lunches. The corollary to that is there are no free lunches.

Second, business leaders and CXOs rightfully dislike burdensome regulations and admire governments whose policies make doing business easier, where policies are predictable, the capacity to implement policies is high, and where bureaucrats and policymakers are responsive to their concerns. A strong leader with few constraints can deliver business-friendly policies much more quickly. Think Modi’s “Make-in-India” push, the hide-and-bide strategy under Deng Xiaoping, and Trump’s promise to appoint Elon Musk as Tsar of Government Efficiency. I found an old article from the New York Times very striking.

In 2004, Apple decided to expand in China with a factory making the iPod, which was becoming a hit product. On a trip to scope out the location for the factory, the head of Apple’s manufacturing partner pointed to a small mountain and told two Apple executives present that the factory would be built there, according to one of the executives. The executives were confused; the factory needed to be up and running in about six months.

Less than a year later, the executives returned to China. The mountain was gone and the factory was operating, the executive said. The Chinese government had moved the mountain for Apple.

While China literally moves mountains, any plan to build a factory in India runs into a thicket of Central and State regulations, NGO protests, and sometimes long court cases. In the US, solar and wind power installations are bogged down by environmental reviews and NIMBYism. The UK, delusionally, in my opinion, opted for Brexit to build a Singapore on the Thames, a low-regulation paradise. Mario Draghi recently lamented how regulations in the EU are stifling productivity growth.

However, I challenge these arguments in class. The skills and structure required to run a large organization are not easily transferable to a country. Countries are not the same as firms. Who is a benevolent and visionary leader with a long-term outlook is apparent only ex-post. And while autocrats can quickly implement good ideas, they can also ram through bad ideas.

Political scientists also distinguish between overt dictatorships (think Syria and North Korea) and informational autocracies. There is no overt suppression in the latter - they hold elections and allow a modicum of media independence but lock in their advantages through a mix of propaganda and policy.

My Take on Democracy

I close by giving the audience a series of facts and thoughts.

1. Most rich countries are democracies. The table below shows the mean and median per capita GDP of democracies vs. non-democracies. I used data on an index of democracy4. Per capita GDP is from the World Bank and measured on a PPP basis.

2. There is not a strong correlation between democracy and growth. The line below shows a weak correlation. For interest, I labeled some obvious outliers. There is a far stronger relationship between political stability and growth. So, you want to be a stable democracy or a stable dictatorship.

3. Establishing the causal arrow from the degree of democracy to growth or development is very hard. They co-evolve. One pattern is that as countries grow and become rich, citizens are less concerned with improvements in material well-being. Instead, they demand freedoms and rights. Put simply, development first, democracy second. This is the modernization theory of Seymour Lipset. South Korea and Taiwan are classic examples of this. Of course, there are exceptions.

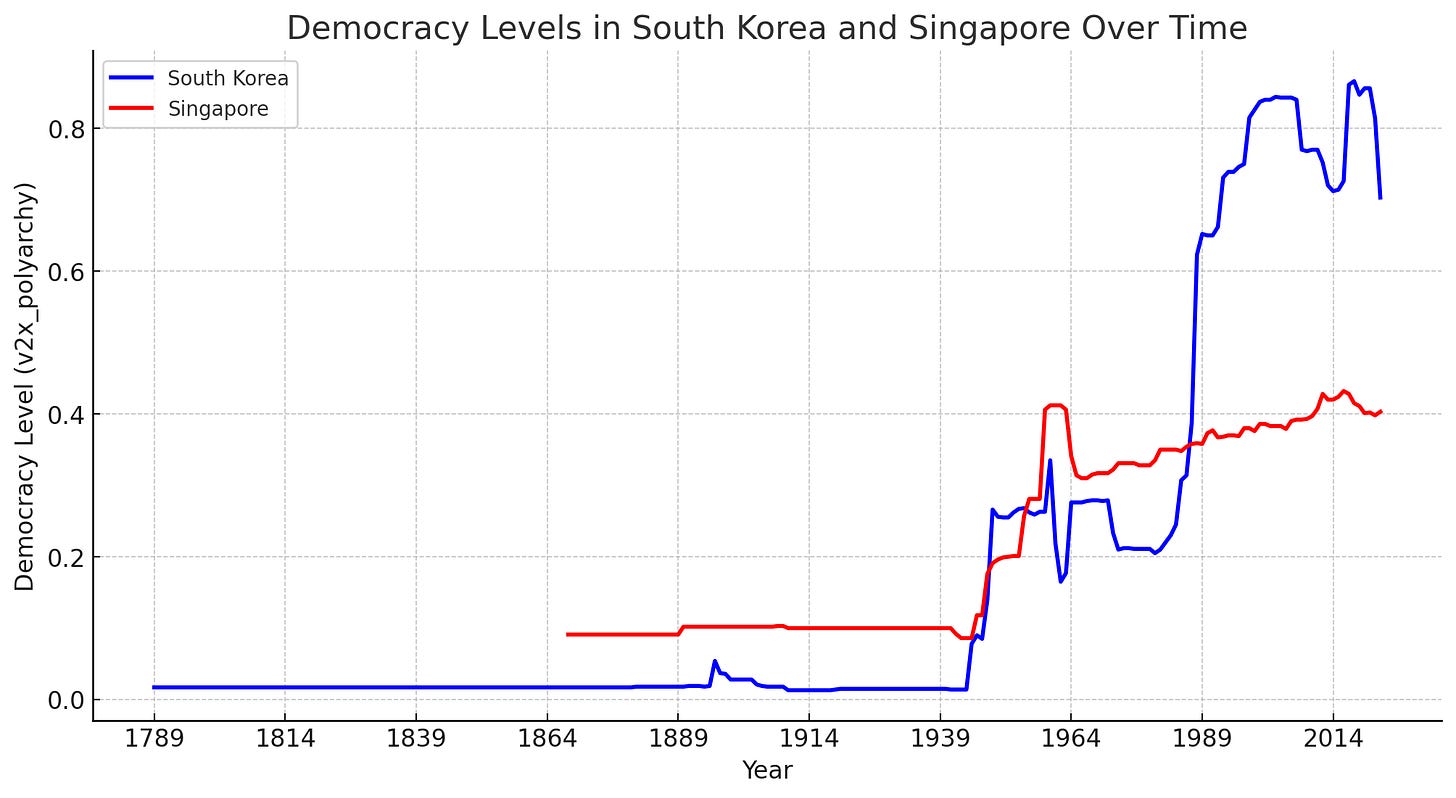

The figure below shows the evolution of democracy in Singapore and South Korea. In Singapore, we observe a gradual improvement in the democracy measure. In South Korea, there was a sharp fall after the coup by Chun Doo-hwan in 1979 and a substantial and sustained jump following the successful democratization (June Democracy Movement).

4. Behind the veil of ignorance, you do not know the autocrat's character, vision, and competence. You are hoping for Lee Kuan Yew, but you will usually get Robert Mugabe, Mobutu, or Papa and Bay Doc. Not a good bet to take.

5. Democracies act as a pressure-release system. Yes, people may throw one set of jokers out, and frustratingly, a new set of jokers comes in. But the alternate is coups, revolutions, blood on the streets, and more virulent forms of political instability.

6. Democracies avoid black swan events – rare outcomes but with massive negative consequences. For instance, famines where millions of people have died occur only in dictatorships. Yes, droughts do happen, but there are no large-scale losses of life. Amartya Sen argues, “democratic governments have to win elections and face public criticism, and have a strong incentive to undertake measures to avert famines and other catastrophes.” Of course, democracy does not solve the problem of hunger.

7. And finally, democracy is good for your soul. Asking whether it is good for stock market returns or GDP growth is the wrong question. Democracy should be seen as intrinsic and not instrumental. The moral needs of all people bend, however fitfully, towards freedom.

INSEAD, like all schools, rewards faculty for high ratings. Yes, the rewards are mainly a pat on the back and sometimes a teaching excellence certificate. But nothing beats that warm fuzzy feeling.

The market rather than shareholder concerns is the disciplining device.

I am not minimizing the atrocities committed by Pinochet’s regime in Chile (1973–90). The dictatorship dealt with opposition to economic reforms by repressing opposition. The growth was also accompanied by an astonishing increase in inequality, with 28% of the income concentrated among the rich 1%.

The democracy index is a continuous measure from 0 to 1.