Last week, I had a Q&A session with CEOs organized by the Wall Street Journal at the Journal House in Singapore. The theme was AI; Supply Chains; Geopolitics and Business; Leadership and Management. While it was a conversation, here are my notes from the event. I added some data as well.

**Q: What are some of the major geopolitical shifts you observe today?**

A: There are three major shifts. First is the rise of great power tensions, particularly between China and the U.S., with fierce competition in global influence, trade, technology, and military power. Historically, some have invoked the notion of the “Thucydides Trap” – when a rising power encounters an established power, conflict is inevitable. Even Xi Jinping cautioned against this trap, saying,

We all need to work together to avoid the Thucydides trap.

Recently, the US and China have started tamping down tensions through dialogue and exchanges.

Second, we see a land war in Europe and a rethinking of NATO's responsibilities. The reliance on the U.S. to keep trade routes open and defend Europe raises questions about Europe's own commitment to its security, especially if Putin extends his ambitions beyond Ukraine. A striking example is the Houthi-led disruption of shipping routes. This impacted mainly Europe-Asia trade, but the world expected the US to step up and provide the global public good of keeping shipping lanes operating. This form of free-riding will be harder in the future as the US focuses inward. Especially if there is a Trump administration next year.

Lastly, there's backsliding on democracy and the liberal international order. We’re witnessing a network of autocrats supporting each other to maintain power, as highlighted in Anne Applebaum's “Autocracy Inc.” This has made the international rules and norms more fragile.

**Q: What lessons can businesses draw from the 2009 Global Financial Crisis and the recent global health crisis?**

A: The 20th century was about efficiency and returns. Questions that businesses considered: How can I organize my supply chain more efficiently? Where should I locate my production? What financial innovations help fund and grow my company globally? The 21st century is shaping up to be about risk and resilience. And here, the crises were a wake-up call.

The Global Financial Crisis taught us the dangers of interconnectedness and the importance of risk management. We re-learned the “no free lunch” principle – a complex CDO yielding 6% and rated AAA and US T-bills yielding 3% implies a free lunch. That we have to pay attention to incentives and governance within organizations. We learned that the term Black Swan has been bandied about with reckless abandon. Financial crises are not that rare.

In COVID, firms learned the importance of contingency plans and war gaming scenarios. Firms should think not just of survival and recovery plans but also of continuity plans. They should think of supply chains not in terms of efficiency but in terms of bottlenecks and collapse. Despite all the digital talk in the last decade, they were ill-prepared when the pandemic hit. Finally, how policy is designed matters. The US policy of giving cash led to a faster recovery compared to Europe’s approach to safeguarding jobs.

**Q: How should businesses go about internalizing these lessons?**

Come to INSEAD. We are good at translating research insights into practical actions for businesses. Here are two examples.

INSEAD has research on how to deal with risk (known unknowns) and uncertainty (unknown unknowns) and how to strengthen decision-making in a crisis. How to combine judgment, data, and expertise. How to avoid biases and leverage the wisdom of the crowds.

We also have research on consumption smoothing, which takes a consumer lens. It analyses how consumers drastically alter behavior in a crisis compared to tranquil times. This allows firms to understand the magnitude of the hit they will take, how long the impact lasts, and how quick is the recovery.

**Q: You’ve outlined the “4 D’s of Disruption” — Demographics, Debt, Deglobalization, and Disasters. How do these impact businesses?**

A: Demographics is a slow-moving but powerful force. Countries like Japan and China face aging populations, which can strain resources and impact everything from healthcare to workforce dynamics. Despite dire warnings, it is not the shrinking of the population but the aging of the population that is more of a problem. Rising dependency ratios mean a shrinking tax base to finance the care needs of an aging population. For businesses, this means fiercer competition for talent, rising labor and pension costs, and a shift in consumer spending away from leisure and food and towards healthcare, medicines, and education.

Debt is another challenge. With the shift from a low-interest rate world to one with elevated rates, businesses must prepare for higher capital costs. The debt dynamics are explosive today, and countries should cut expenditures and bring down debt. But three things are stopping this: the rise of populism means that all politicians are promising more and more spending in an inflationary environment. Second, geopolitical tensions mean rising defense expenditures and subsidies for revitalizing manufacturing. Third, the aging population means that health costs are rising. With fiscal policy absconding, monetary policy will be the only game in town. Central Banks will be forced to keep interest rates high. And the days of QE and ZIRP are over. Therefore, businesses should prepare for a world of elevated interest rates. At the same time, those with access to cheap capital, say internal cash reserves, will benefit in such a world.

Deglobalization, driven by geopolitical tensions, pushes businesses to rethink their global footprints. If we move to a China plus one world, most businesses will be able to manage this. Alternatives like Vietnam, Indonesia, and India present opportunities and challenges – India has the scale but lacks infrastructure, sufficient middle-skilled workers, and steep regulatory hurdles. Vietnam is a mini-China but lacks the scale. Indonesia is somewhere in the middle.

Disasters, both natural and economic, remind us that resilience is key. But these are impossible to forecast – businesses can only prepare for them.

**Q: How can businesses navigate the complex dynamic between the U.S. and China amidst trade and technology wars?**

A: There is nothing that I can say that all of you do not know. Yes, you will have to think about resilience. Yes, you will have to think about nearshoring and friend shoring. Yes, you should contemplate a China-plus-one strategy. Yes, you must play a delicate balancing game between different governments, shareholders, and customers, who will pull you in different directions.

But here is a question to consider. COVID was a seismic shock. In the beginning, we had literally zero historical cases for comparison. Many of you took actions – some worked, some did not. What lessons did you learn, and how did you formalize them? What processes will you activate? What information do you need to collect? What stakeholders should you alert? Creating processes to organize for a crisis is too late when the crisis has started. So the big question is, will you be ready the next time a crisis hits?

In my opinion, most senior executives look at the crisis through rose-tinted glasses. The fact that they survived and then did well after vaccines came out is all they remember. I suspect many have not formalized the lessons from COVID. COVID was a supply shock, and the geopolitical tensions, if they explode, will have a similar flavor.

**Q: What are some concrete things that businesses should do**

Here are three concrete things.

Singapore has a Strategy Group called Center for Strategic Futures that sits inside the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office). You need something similar. Call it a Division for the Future. Staff it with a diverse set of people, with specialists and polymaths. Build capacity, expertise, and tools on a) future trends, b) surprises, and c) discontinuities and disasters.

Put processes in place – informational, organizational, and communication –that can be activated when crises happen.

Data data data. There is a trade war brewing. Here is how it will get played out. As tariffs increase, firms will react by trying to evade them. They will set up in Vietnam, Mexico, etc. The US and European governments will eventually ask you to measure and report the Chinese content in exports and production. Europe’s carbon border adjustment mechanism requires firms to measure the carbon emitted during the production of goods entering the EU. Do you have the ability to do these calculations?

**Q: What other shocks do you foresee, and what headwinds do businesses face?**

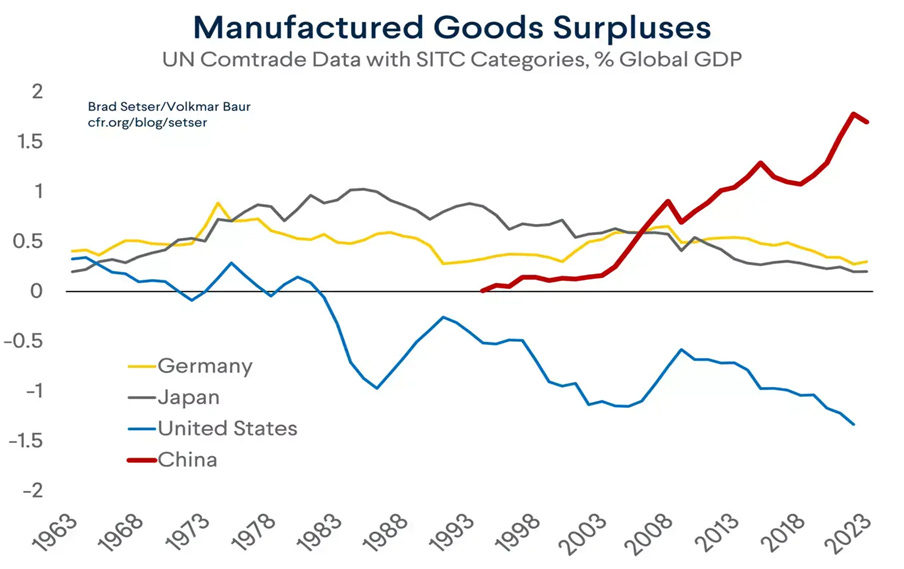

A: A significant headwind is the "Second China Shock." The first China shock started when China joined the WTO, which led to deindustrialization in some regions and countries (see manufacturing employment in the US below).

Today, as China struggles with deflation and deficient internal demand, it seeks to export its way out of trouble, creating competitive pressures globally.

Advanced countries fear deindustrialization. Emerging markets will find it harder for others to join the global value chain. This is triggering protectionist measures not just in the US and Europe but also in India, Brazil, Chile, etc.

The AI race is another evolving trend. Historical precedents show that the last three industrial revolutions also triggered geopolitical shifts in power. Will the AI race do the same? Countries that can innovate, adapt, and integrate AI effectively will gain significant advantages in the global arena.

**Q: How can businesses mitigate risks and prepare for future shocks?**

A: The key lies in resilience and adaptability. Creating robust contingency plans, diversifying supply chains, and investing in continuous learning and innovation are essential. Understanding the interconnectedness of global risks and actively planning for them can make the difference between merely surviving and thriving amidst disruptions.1

**Q: Finally, what opportunities do you see in this era of deglobalization?**

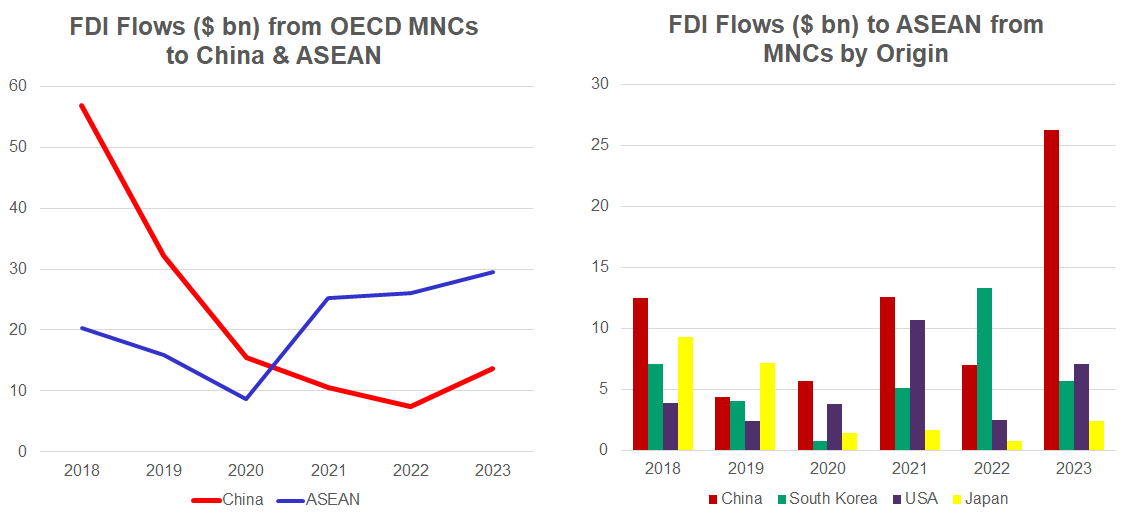

A: While some countries may lose out, others stand to gain. If I look at FDI flows in this region, FDI flows to China from OECD countries have collapsed from $60 billion to $10 billion. In the meantime, flows to ASEAN countries have tripled from $10 billion to $30 billion. More interestingly, the biggest investor in ASEAN countries is China – investment flows have tripled between 2022 and 2023. These are opportunities for countries.

To the extent there is no armed conflict, we see a reshuffling. Companies that can effectively navigate these environments and tap into local strengths will be well-positioned to capitalize on the shifting geopolitical landscape.

Closing Thoughts

The US and China should realize that they must cooperate and compete. Focusing on competition alone and a zero-sum mentality creates a skewed picture - it sees every action as threatening even if it does not affect vital interests; it sees other countries as pawns, not partners. They must recognize their interdependence - in trade, flows of ideas, people, and technologies. US’s efforts to stop the flow of technology will fail for a simple reason. Knowledge leaks! And paradoxically, the restrictions increase the incentives.

Neither side can impose its will on the other. Instead, each should nurture its own sources of strength rather than degrade the other. The US does not get to choose China’s future, its regime, or the size of its economy. Neither should China underestimate the resilience of the US and its ability to do the “right thing after it has tried everything else.”

However, they should be realistic about their differences in governance, economic models, the role of the state, the relative importance of individual rights vs. social stability, global alliances, views on regional security, etc.

Not a satisfactory answer, in my opinion. Too general and non-falsifiable.